Lately, there’s been a lot of hullabaloo about hiring for qualities like attitude, adaptability, and emotional intelligence. And it’s not hard to see why: The World Economic Forum's latest Future of Jobs Report predicts that, as things change at record speed, nearly 40% of today’s jobs will either change or become obsolete in the next five years.

Naturally, employers are looking for people who can think, act, and adapt. So candidates’ soft skills, values, and behaviors have (in my opinion, deservedly) been put on a pedestal.

But there’s an issue: These “soft qualities” are open to interpretation, making them fertile ground for one of the most dangerous hiring traps out there: affinity bias. Put simply, “affinity” is a natural liking, and the bias kicks in when we start unfairly favoring people who feel familiar to or remind us of ourselves in some way.

If you’ve ever selected someone just because you share an alma mater, a sense of humor, religion, race, gender, or career path with them, understand this: It can blur your view, lead to poor hiring choices, and hamper your company’s diversity all at once.

So, how can we put the affinity bias in hiring to rest? I asked several industry experts for insights on how it can show up in real-life recruitment, and got their take on how to prioritize culture, traits, and soft skills without letting the comfort of “familiar” cloud your judgment.

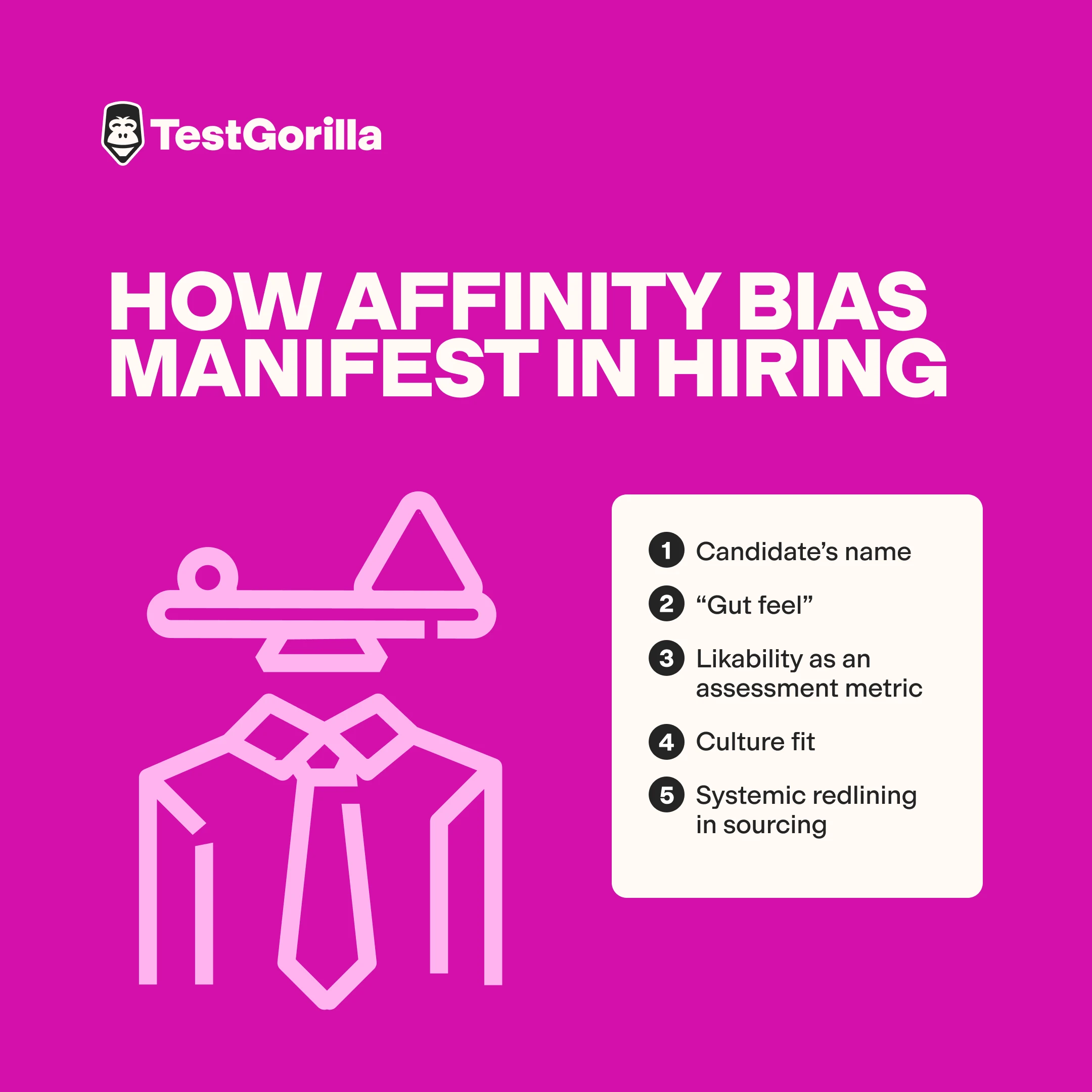

How affinity bias can manifest in every stage of hiring

Before we get into the solution, we first need to map out the problem. Matt Collingwood, Managing Director of VIQU IT Recruitment, tells TestGorilla that affinity bias is a “real issue within recruitment” because, truthfully, “we all carry some level of unconscious bias with us.”

And the biggest challenge with affinity bias is exactly that: It's typically “unconscious,” and you can’t fix something if you don’t even know how or when it manifests.

Let’s look at how the affinity bias creeps into recruitment.

What’s in a (candidate’s) name? Affinity bias hiding in plain sight

Even people familiar with affinity bias believe it’s just about sharing similar backgrounds, interests, or personality traits. But it can show up in far subtler ways, including in something as simple as a candidate’s name on a resume.

Kaomi Joy Taylor, Founder and Chief Namiac at The Museum of Names, has spent her career studying this. She tells me:

“Most people don’t realize the everyday name bias in their companies. For example, research shows that pronunciation bias is common. The degree of hiring prejudice faced by minority candidates often corresponds to how ‘easy-to-pronounce’ the hiring managers perceive their name to be, which, in turn, aligns with what is most familiar.”

As Taylor says, there’s much research to support this view.

One study found that people form more positive impressions of individuals with easy-to-pronounce names than those with difficult-to-pronounce names because the latter are perceived as less familiar. And this has real-world implications, as the study also found that people with easier-to-pronounce last names occupied higher-status positions in law firms.

Another study showed that sellers on online platforms offered better deals to buyers whose names began with the same letter as theirs. This supports the notion that even a single letter of someone’s name on their resume can trigger unconscious favoritism.

”Gut feel” that can lead to discrimination

Ever thought, “I clicked with this candidate immediately,” or “I really like them,” but couldn’t put your finger on why? At some point, most recruiters or hiring managers have had a “gut feel” about a candidate and mistaken it for fact, when really it’s affinity bias in disguise.

Research shows that managers openly admit to using their intuition in making decisions about people’s performance, personalities, and person–environment fit. This instant attraction can color how positively you perceive a candidate's capabilities, how warmly you interact with them, and even how leniently you question them in interviews.

Collingwood tells TestGorilla how this has played out in his own experience as an interviewer:

“I found that if I liked someone, my line of questioning would often be softer, but if I did not click with a candidate right away, I might press harder, asking tougher and more critical questions. However, this meant that I sometimes gave the easier interviews to people who were not ultimately the right fit, while giving stronger candidates a rougher time and not realizing their potential.”

The scary part is that the problem doesn’t stop at making a wrong hire or missing an opportunity to snag someone great. If a candidate suspects that they’ve been mistreated based on personal traits, they could file a discrimination claim under the US Civil Rights Act of 1964 – a risk that can cost you financially and in your reputation as an employer.

Likability as an assessment metric

When we call someone “likable,” we usually mean they’re easy to be around – charming, friendly, pleasant. I can see why employers value that, especially for customer-facing, sales, or partnership jobs.

But Edward Hones, owner of Hones Law, warns that likability is actually “masquerading as a qualification.” And he may be onto something.

After all, likability is a slippery, subjective trait. What does it really mean, and to whom? Without clear behavioral markers defining what “likable” looks like in practice, hiring teams will default to choosing people they personally like – those who feel “just like them.” That’s exactly how affinity bias sneaks in.

Making decisions based on how much you like someone is both unfair and risky. An analysis of 10,000+ interviews found that interviewers were more likely to hire someone if they liked their personality. But these hires can come back to bite you: The report indicates that prioritizing likability over capability can lead to costly turnover and legal repercussions.

Culture fit: affinity bias’s biggest crutch

Culture fit has become central to hiring, and that’s not a bad thing. The people you hire should share your company’s values and working practices, and be compatible with the rest of the team.

Unfortunately, many hiring teams take “fits our culture” to mean “similar to us.” They end up prioritizing candidates who are from similar backgrounds to existing team members, share slang and inside jokes, and even align with them in after-work hobbies.

And sometimes, hiring professionals do this knowingly.

In a qualitative study of UK recruiters, researchers found “organizational fit” is often consciously used to shut people out at three stages:

Briefing. Criteria for organizational fit – something recruiters felt employers “will not compromise on” – were often not explicitly defined in job descriptions or briefs that recruiters receive from employers. Instead, the criteria were implied and could be exclusionary. One recruiter explained that a job description requiring two years of experience suggests the employer wants a candidate in their 20s – and older applicants would be rejected.

Recruitment. One recruiter suggested that she’d likely recommend an entertaining, charismatic candidate if she knew the hiring manager liked people with a sense of humor. Another said that when she hired for a company that had a “very quiet” environment, she rejected a candidate who “had all the skills” because they were “very bubbly” and would “piss someone off.”

Selection. Recruiters involved in the study said they often felt hiring managers excluded candidates based on whether they shared characteristics similar to their own or those of their team. Those include gender. One recruiter shared:

“I was recruiting for a finance manager in the retail fashion company, and the guy that I had ticked literally every single box on the specification. [...] If he didn’t get the job, I just couldn’t understand why.

After doing a bit of digging, [...] I found out that their team was all women. [...] They kind of said, ‘We’re not really allowed to say we wanted a woman. But a woman would fit fantastically in our team. We’re not being sexist.’”

Systemic redlining in sourcing

Affinity bias can also rear its ugly head when you don’t choose and use your sourcing channels wisely.

When you keep going back to the same universities, you risk sourcing people with similar educational and socioeconomic backgrounds. Over-relying on job boards can have the same outcome: Certain groups are often overrepresented on specific platforms.

And going overboard on employee referrals can be the biggest culprit of all.

Referral-based hiring often reflects our existing networks, which tend to mirror who we are. That means people usually refer others with similar backgrounds, experiences, or even gender and race.

For instance, one study found that smaller firms are more likely to hire (and less likely to fire) individuals of the same race as the founder. The study also showed that referral-based hiring helped explain why employees of different races weren’t equally represented in senior roles.

More recently, in another field study, 71% of female participants and 75% of male participants referred job candidates of their own gender.

These studies show that affinity bias rising from referrals can even lead to gender and racial biases.

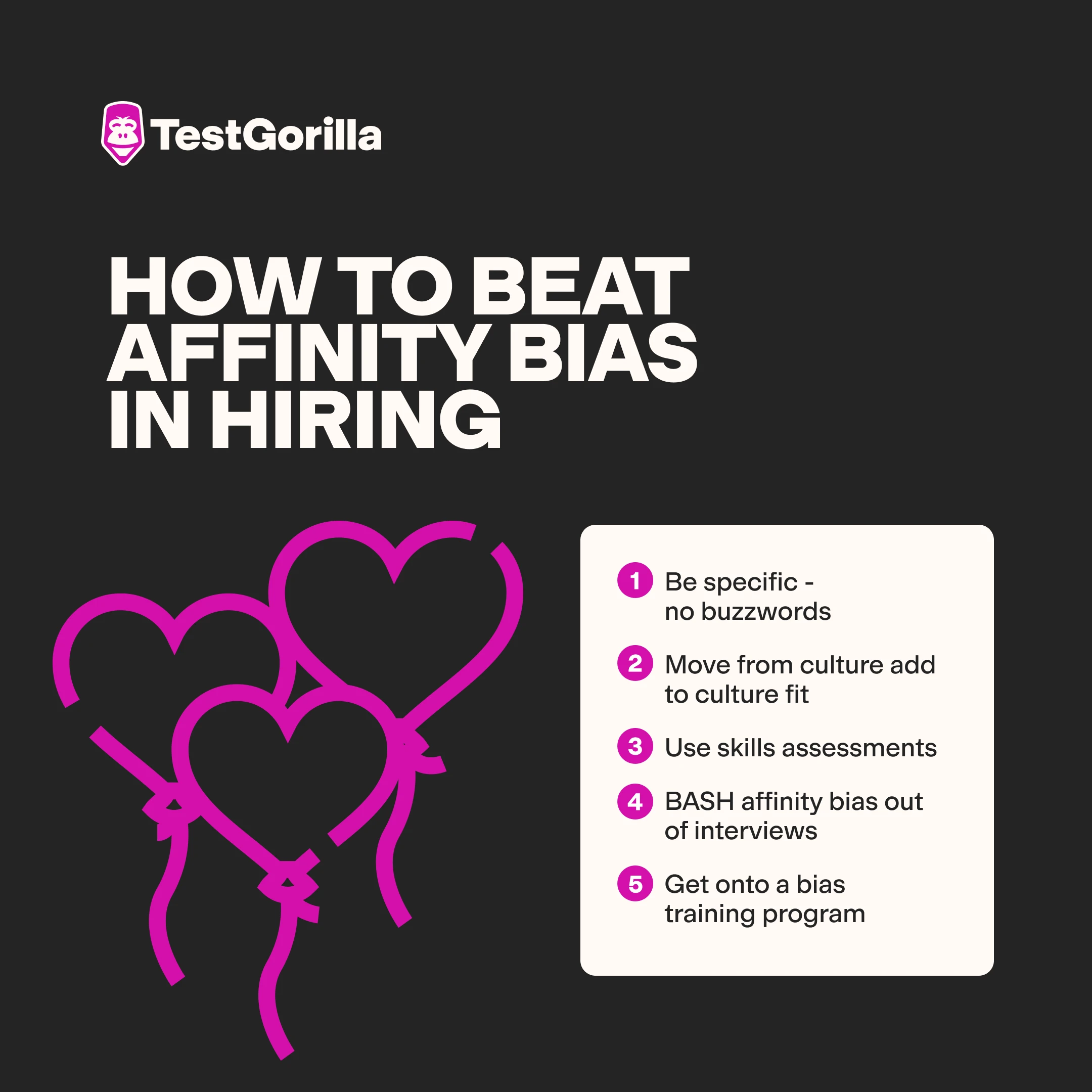

Fighting back: How to overcome affinity bias in hiring

Affinity bias may often be invisible, but it’s never invincible. Here’s how you can beat it:

Goodbye, buzzwords – hello, specificity

We’ve already seen that when you leave concepts like likability open to interpretation, decision-makers often simply select candidates who seem similar to them. One way to tackle this quickly is by defining what “likability” means for the job in terms of concrete, observable, and measurable behaviors.

For instance, Stephanie Manzelli, Chief People Officer at Employ Inc., suggests. “Instead of simply saying ‘collaborative,’ measure behaviors like ‘seeks input before making decisions’ or ‘shares credit openly.’” Similarly, if a “likeable” candidate is someone with empathy for customers, define that as “truly understands customer goals and pain points before providing tailored solutions.”

Don’t stop at definitions; incorporate these defined behaviors into your job descriptions, hiring criteria, and scorecards. Leave no room for subjective, affinity-based interpretations at any stage of the hiring process!

Culture add > culture fit

It can be hard to explain to hiring managers and other stakeholders that culture fit doesn’t mean hiring people who are just like the existing team. Even when they do understand, they often slip back into old habits and use the idea of culture fit to justify choosing candidates who feel familiar.

So, what can you do instead? “The solution is shifting from culture fit to culture add,” Manzelli says.

At TestGorilla, we’ve been advocating this approach for years. Culture add means moving away from hiring people who “fit in” and toward hiring people who make your company culture stronger and more complete. As Manzelli puts it, it’s about asking, “What unique perspective, skill, or experience could this person bring that we don’t already have?”

Even a tiny change in how you label and define cultural contributions can move the needle and reduce the likelihood of affinity-based decisions. But how do you actually make that shift?

“Start by clearly defining your company’s core values, such as curiosity, integrity, or customer obsession,” Manzelli advises. “[Then], in interviews, test for those values and intentionally probe for differences that might stretch the team's thinking.”

For example, she suggests giving candidates a prompt like, “You're behind on a deadline, but uncover a major data error. Do you escalate, delay, or push forward?” How candidates handle tough moments like that can reveal a lot about their values – and the unique strengths they bring to the table.

That said, interviews only tell part of the story. They’re still vulnerable to various biases, so it’s important to back them up with something more objective.

Skills assessments: The ultimate antidote

One simple way to kill affinity bias in hiring is to start your process by confirming what candidates can actually do. It’s like Hones tells TestGorilla: “Gut instincts are fine, but they should be tested, not trusted.”

That’s where skills-based testing comes in. When you assess real-world skills first, you give yourself – and everyone involved in hiring – clear evidence of who can actually do the job. Suddenly, a last name on a resume or a shared interest matters way less because you can see candidates’ abilities in black and white.

Research shows that employers are increasingly recognizing the importance of this approach. Our 2025 State of Skills-Based Hiring report found that 76% of employers use skills tests to validate candidates’ capabilities.

And skills assessments aren’t limited to technical abilities like coding, programming, or accounting. You can also test for soft skills, cognitive abilities, personality traits, and, yes, even culture add.

Evaluating these qualities through formal assessments removes ambiguity, guesswork, and any resulting affinity bias from the equation. Plus, it improves hiring outcomes. For example, one study found that employees who were selected using a formal culture-fit measurement system performed significantly better than those selected without one.

🤔 What about sourcing? Skills testing is a stellar way to reduce affinity bias in active hiring scenarios, but what about when you’re building a pipeline of passive candidates? You can’t ask everyone who might be a fit in the future to take a test… The solution is pre-vetted sourcing pools like TestGorilla’s. With TestGorilla Sourcing, you can access more than 2 million diverse, skills-tested candidates – so you can stop relying on the same schools, job boards, and referrals that reinforce bias. |

BASH affinity bias out of interviews

There’s no magic fix for affinity bias in hiring, but you can chip away at it with what I call BASH: blind interviews, AI interviews, structured interviews, and human accountability. Each tackles bias from a different angle, and together they make your interviews fairer and more consistent.

Blind interviews are conducted by interviewers who don’t know candidates’ backgrounds, demographics, hobbies, alumni, or even names. Research shows that this helps prevent the risk that interviewers will enter discussions thinking a candidate is “just like me.”

AI interview tools can handle early candidate screening without human involvement, reducing the likelihood of bias creeping in. One study found that 78% of candidates prefer AI interviews and reported feeling less bias than in human-led ones.

Structured interviews: Remember Collingwood’s story about asking easier questions to candidates he “clicked with”? Structured interviews help prevent that from happening by asking every candidate the same predetermined list of questions and scoring them against the same clear criteria. Hones tells us that when his team stopped relying on gut feeling and switched to structured interviewing, “the result was transformative.” He shares, “Within six months, we brought in talent with far more diverse perspectives who ended up outperforming previous hires in both client satisfaction and retention.”

Human accountability: Finally, ask interviewers to explain their decisions – in notes, debriefs with the hiring team, or panels to discuss candidate selections. As Hones explains, “When interviewers force themselves to articulate why someone is strong or weak, based on evidence rather than chemistry, bias naturally loses its grip.”

Get off the bias train and onto the bias training program

You can source right, build scorecards, use AI tools, and put candidates through all the skills tests in the world – but ultimately, hiring decisions sit with humans, and if they really want to pick who they’re vibing with, there’s a chance they will.

So, you must provide unconscious bias training to everyone on your hiring team. You can do this in-house through your learning and development team (if you have one), hire an external trainer, or create your own interactive program with real-life examples of affinity bias, mock drills, and more.

The best insights on HR and recruitment, delivered to your inbox.

Biweekly updates. No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Contributors

Edward Hones, Hones Law, Owner

Kaomi Joy Taylor, MPA, The Museum of Names, Founder and Chief Namiac

Matt Collingwood, VIQU IT Recruitment, Managing Director

Stephanie Manzelli, Employ Inc., Chief People Officer

Related posts

You've scrolled this far

Why not try TestGorilla for free, and see what happens when you put skills first.