We like to think gender doesn’t dictate our choices – we’ve pursued our careers because of unique interests, and this is true for the rest of the population, too.

Yet, the data suggests otherwise.

On average, women send almost 12% more applications to service occupations than men. They also send fewer applications to machine, craft, and construction roles than their male counterparts, even when they come from similar educational and occupational backgrounds.[1]

These application differences have knock-on effects for industry demographics – and not just in favor of men. Many people know construction is male-dominated, but did you know there are twice as many women as men working in customer service?[2]

The roles in which women are overrepresented are known as “pink collar jobs.”

To attract more diverse candidates to these roles (and reap the rewards of doing so), employers need to first understand where these trends come from.

Let’s start with the term “pink collar jobs.”

Table of contents

What are pink collar jobs?

Social critic Louise Kapp Howe coined the term “pink collar jobs” in the 1970s to describe jobs almost exclusively performed by women.[3]

These roles fell outside the usual categories of white-collar or blue-collar workers, and they were often lower-paying. Types of jobs included:

Beauticians and hair stylists

Florists

Sales clerks

Secretarial work and typists

The term is now used to describe any role dominated by women, and many of these roles remain the same as when Kapp Howe first popularized the phrase.

However, the advent of digital work and the expansion of the middle class means pink collar jobs have diversified.

There are now many professional roles considered pink collar jobs, often because they are related to gender stereotypes of “feminine” pursuits like caregiving rather than more “masculine” ones like mechanics or robotics.

An example of a pink collar job of this type is interior design: 69% of interior designers in the United States are women, compared to just 18% of architects.

What’s the difference between pink, blue, and white collar jobs?

The term pink collar jobs comes from the term blue collar jobs, but the difference between the two isn’t as simple as “pink is for girls, blue is for boys.” That would leave a big question mark over who white collar jobs are for… ghosts?

Here is a breakdown of the differences between these terms.

Type | Features | Name derives from |

Pink collar job | Women-dominated; Usually falls outside of the categories of blue-collar and white-collar workers; Often low-paid; Often derives from associations with women having emotional intelligence | The idea of pink as a “woman’s color” |

Blue collar job | Occurs in a non-office setting, such as outdoors or in a factory; Usually low-wage work with limited progression, paid hourly; Frequently considered “low-skill”; Almost always involves manual labor; Often male-dominated; Examples include construction workers, truck drivers, and factory workers | The coarse denim shirts commonly worn by agricultural and manual laborers in the 20th century |

White collar job | Occurs in an office setting; Mostly well-paid, salaried workers; Offers avenues for progression up a corporate hierarchy; Usually requires higher education | The white shirts worn by male office workers in the 20th century and today |

But where do pink collar jobs come from?

The history of pink collar jobs

There is a common misconception that working women are a 20th-century phenomenon. In fact, women have always existed in the world of work, albeit restricted to certain roles.

Pre-World War I

One of the earliest pink collar jobs was nursing, which Florence Nightingale famously feminized in 1860 when she declared that “every woman is a nurse.” She even said men were not suited to nursing due to their “hard and horny hands,” which were too rough to dress wounds.

By 1900, women made up about 18% of the US workforce, mostly working in domestic and personal services, like servants, housekeepers, or seamstresses.

The growing feminist movement meant wealthy women could attend college and practice highly skilled professions like medicine and law, but these were a small minority.

World War I and World War II

World War I brought huge changes for women. With Western men away fighting, women became central to the war effort, taking up jobs as:

Ammunition testers

Switchboard operators

Stock takers

Agricultural workers

… and more.[4]

They were paid less for their labor since it was temporary, and there was backlash against women’s employment once the war was over, with calls for women to return to the home.

However, their value to the war effort couldn’t be ignored. In the UK, women over 30 were given the right to vote in 1918, a move widely read as a “reward” for women’s work during the war effort, and it was a similar story in the US after the war.

1950s – 1970s

After WWII, women took on pink collar jobs to remain employed and gain some much-needed independence without facing extreme judgment.

Despite the prevailing image of the 1950s stay-at-home mother, almost a third of all married women in the US in 1960 were employed – more than double the figure in 1940 – and overwhelmingly in pink collar jobs.[5]

The Equal Pay Act was passed in the United States in 1963 to address this social issue, though the still-limited welcome for women across industries hampered its efficacy in reducing the pay gap between men and women.

1980s to the present day

The percentage of women as part of the overall labor force worldwide climbed steadily from 1990 to 2005, when it peaked at 39.9%. In the US, women now make up 46.1% of the workforce.

However, these roles are still spread unevenly across industries. While women have made gains in some male-dominated industries, in many cases their numbers are still disproportionately low.

An example is STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math). In 1970, just 8% of workers in STEM were women; in 2019, this was up to 27%.[6]

The types of pink collar jobs out there have shifted somewhat in recent years, partially thanks to the boom in the beauty industry. The number of manicurists in the US has tripled since 1985.[7]

However, many pink collar jobs have stayed the same. Nursing is one of them. The number of male nurses is growing but still incredibly low. Although it has risen from 6.6% in 2013, men still made up less than 10% (9.4%) of registered nurses in 2020.

In fact, many pink collar jobs are becoming even more women-dominated. One-third of public school teachers in 1980 were men; this has shrunk to just more than 25% today.[8] [9]

Examples of pink collar jobs

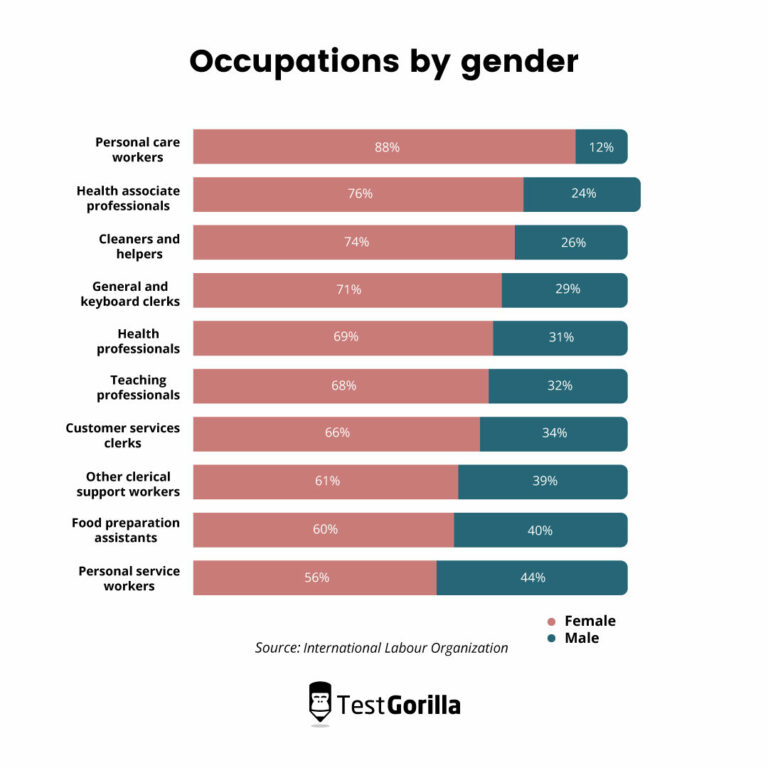

According to the International Labor Organization (ILO) and based on worldwide data, the field with the highest proportion of women is personal care workers, which includes positions like health care aides.

In fact, healthcare accounts for more than one of the top 10 most women-dominated fields in the ILO’s list, with women accounting for:

88% of health associate professionals, including pathology, imaging, and pharmacy

69% of health professionals, including medical doctors and nurses

There are many skills encapsulated in these jobs – for example, a healthcare assistant requires communication and numerical reasoning skills and may benefit from knowing other languages, like Spanish.

The pink collar jobs that have remained the same since the 1970s include keyboard clerks, teaching professionals, and clerical support workers.

These roles require fast typing skills and other professional skills like self-efficacy, communication, and time management.

What are examples of male-dominated jobs?

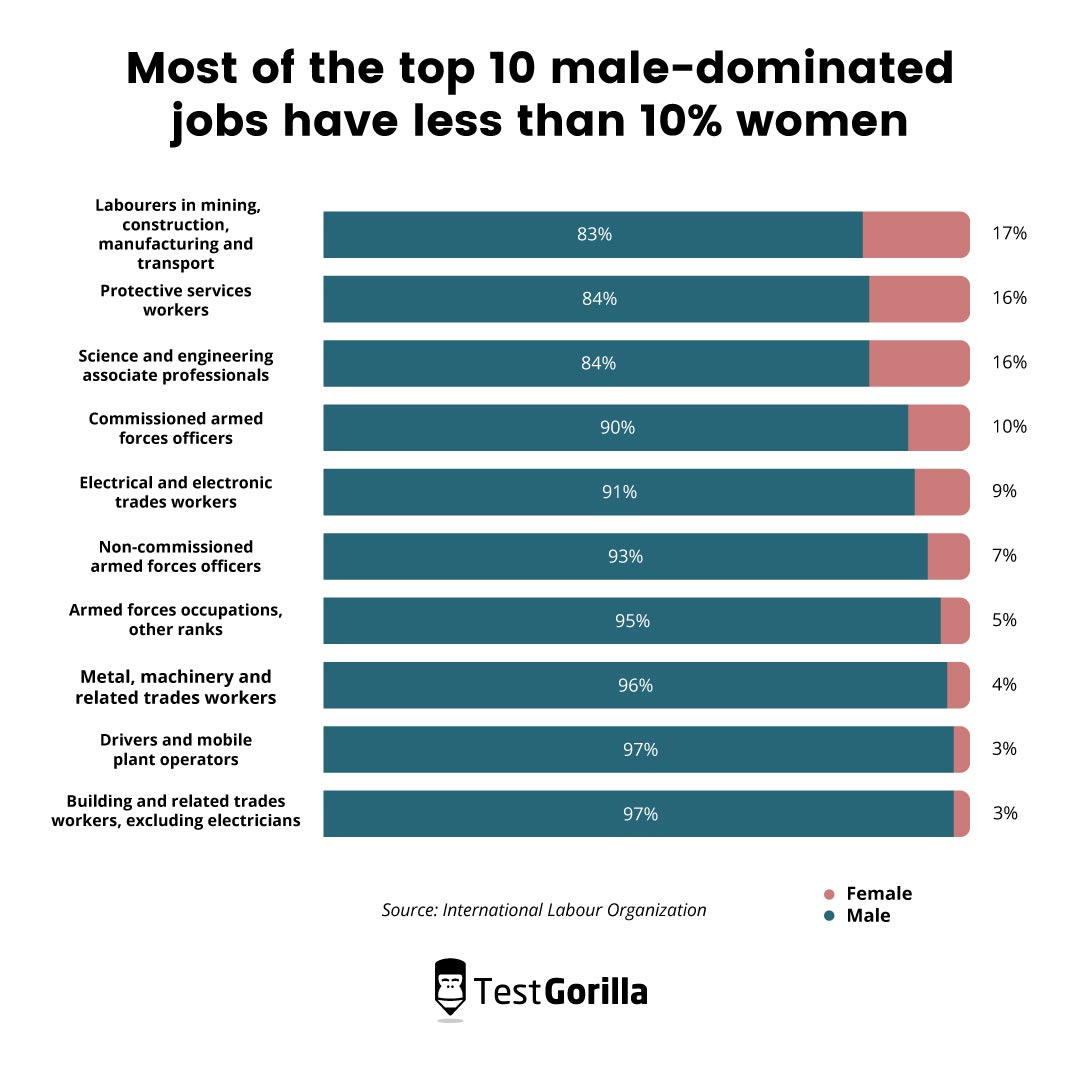

The above view of women’s dominance in pink-collar work seems shocking – until you look at the rest of the ILO’s list. Most of the roles on this list are male-dominated, with many of the most acutely male-dominated being blue collar professions.

Seven of the top 10 most male-dominated jobs have less than 10% women, including building workers, metalworkers, and armed forces occupations.

Clearly, the issue of women’s dominance, even in so-called “pink collar jobs,” is not as pronounced as male dominance in many sectors. However, the reasons behind the gender split in these industries are intertwined – namely, gender roles.

Why are pink collar jobs female-dominated?

As we can see from the history laid out above, when women began to enter the workforce en masse, they were most successful in professions that aligned with the roles and expectations placed on them outside the workforce.

These were frequently roles requiring emotional labor: the requirement for workers to manage their own and others’ emotions. Nursing and social work fit with women’s nurturing role; teaching was seen as an extension of motherhood.

Part of the reason these trends persist is that these expectations do. Women are still expected to prioritize childcare.

During the pandemic, for example, women with children under 10 were considering leaving the full-time workforce at rates 10% higher than men in the same group.[10]

These expectations may influence not only a woman’s likelihood of encountering bias or discrimination, but also her skills and preferences.

This is because they affect how individuals are socialized. Many studies have investigated the differences in how boys and girls are taught to express their emotions, and research shows parents talk about emotions more with daughters than sons.[11]

This could well contribute to women’s perceived aptitude for “nurturing” roles, and it’s surely a contributor to the gender application gap we mentioned at the start of this blog.

From this, it’s clear why pink collar jobs exist, but the real question is: Why do they persist? And why is the issue intensifying over time, despite the strides we’ve made for equality in the past fifty years?

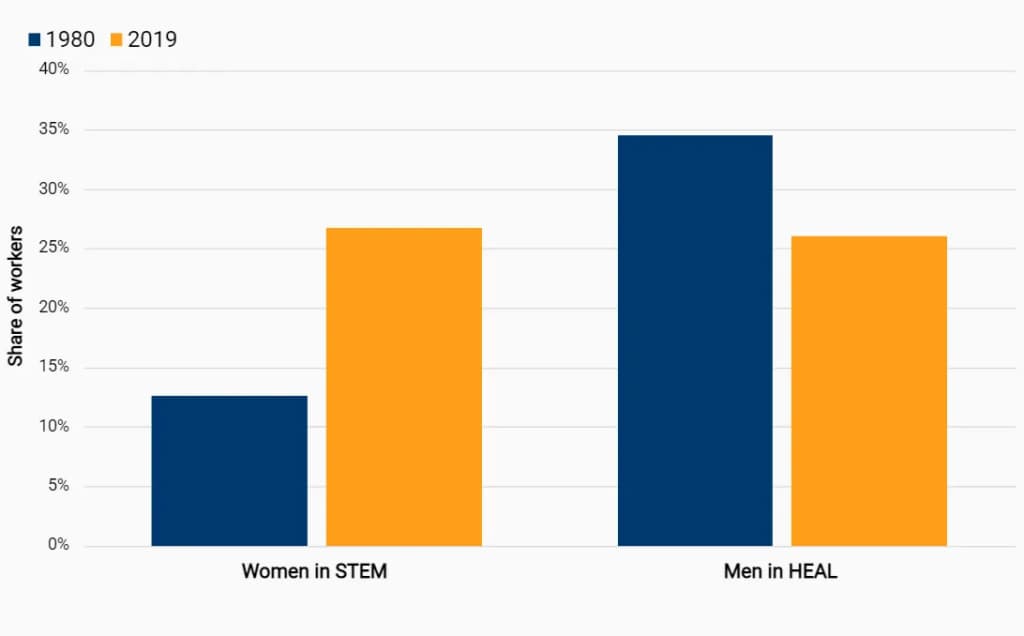

The reason is that, as author Richard Reeves points out, women have broken down barriers into so-called “men’s jobs,” but men haven’t achieved the same with pink collar jobs.

Reeves calls the most common pink-collar careers “HEAL” jobs: jobs in health, education, administration, and literacy. He frames HEAL as the opposite of STEM.

The proportion of men in HEAL roles has drastically reduced since 1980, even as women have made great strides in STEM:

This is not always for lack of trying from men. Take teaching: The decline in the proportion of male teachers is not due to diminishing interest amongst men in the profession.

On the contrary, the number of male teachers employed in public schools has grown faster than the rate of increase in the student population, at 31%. However, the number of women entering the profession has increased at more than twice this rate.[8]

This is likely due to the increase of women entering the workforce more generally, particularly in the US. As they still overwhelmingly opt for HEAL roles, it makes sense the proportions of women in some of these industries continue to grow.

Clearly, despite shifting expectations of women allowing for their greater participation in the workforce, more needs to be done to attract people of diverse gender identities to pink collar jobs.

Much of this must happen through societal change: widening our expectations for boys and men, and celebrating nurturing qualities in people of all gender identities.

However, there are things individual organizations can do to move the needle in your open roles.

6 best practices for attracting diverse candidates to pink collar jobs

Gender equality in the workplace benefits everyone – not just women.

Pipeline research found that for every 10% increase in intersectional gender equity, organizations achieve a corresponding 1%-2% boost in revenue.

The benefits aren’t just financial. Finnish research shows children achieve higher scores on national exams when they are taught by a gender-balanced staff.[12]

This is not just about equality within a binary, either, but about making your organization accessible to people of all genders. That means attracting non-binary and trans candidates as well as cisgender men and women to your organization.

Assuring diversity can help you hang onto your best people; research suggests higher levels of gender diversity, as well as HR policies specifically focusing on these issues, correlate to lower employee turnover.

The best practices we’ve outlined below are all about removing bias from your hiring process and attracting and retaining a broad range of candidates. For that reason, many of them will not only apply to hiring for pink collar roles, but also roles outside the pink collar umbrella.

Best practices for attracting diverse candidates to pink collar jobs: Summary table

Eager to get started? Here’s a quick summary of our top tips.

Hiring for pink collar jobs best practices | Example actions |

Use gender-neutral language in your job ad | Avoid third-person pronouns like “he” or “she,” instead addressing the reader as “you” |

Hire for skills over experience | Use skills testing instead of resumes to screen candidates |

Take a structured approach to interviews | Ask all candidates the same questions in the same order |

Hire for culture add, not culture fit | Test for culture add during screening and follow up with questions like “How important are empathy and kindness when working in a team?” |

Use skills-based learning to promote internal mobility | Log workers’ performance on skills tests into an internal talent marketplace and use this to identify opportunities for growth |

Promote psychological safety in the workplace | Supply multiple avenues for pink collar workers to raise concerns so they can do so in a comfortable way |

1. Use gender-neutral language in your job ad

Writing a great job description is more of an art than a science, but you don’t have to be a poet to write an inclusive job ad. The key is to use gender-neutral language:

Avoid third-person pronouns like “he” or “she.” Address the reader as “you.”[13]

Include only essential skills requirements and the attributes needed for the role.

State your commitment to diversity and inclusion.

You might consider reducing the number of gender-coded words you use in your job descriptions – or using a mix of them so that candidates of any gender can find something they relate to. Here are some examples:[14]

Male-coded words | Female-coded words |

Active; Adventurous; Aggressive; Ambitious; Assertive; Autonomous; Challenging; Competitive; Decisive | Affectionate; Cheerful; Committed; Compassionate; Connected; Considerate; Cooperative; Empathetic |

Also avoid using job titles associated with one gender, such as waitress or stewardess, and use gender-neutral titles like server or flight attendant.

This helps you be inclusive of LGBTQ+ candidates and men in pink collar jobs.

2. Hire for skills over experience

Once you’ve attracted a diverse range of candidates, it’s time to screen and assess them. The best way to do this fairly is by using skills testing instead of candidates’ past experience.

Part of the reason pink collar roles persist so stubbornly is employers’ overreliance on resumes and years of experience during the screening process, which makes it harder for women and men to break into new industries.

Furthermore, neither of these things reliably show you a candidate’s skills and instead rely on an honor system.

Skills testing, on the other hand, enables you to directly test the skills candidates will use in the role. The tests for a Registered Nurse would include essential skills like:

Critical thinking

Problem-solving

Time management

According to a study at Google, skills testing was 10 times more effective at predicting job performance than years of work experience, which was only 3% accurate.[15]

Work experience is also not a good predictor of retention.

The final big benefit of skills testing is that it empowers you to compare candidates with ease and precision, instead of falling back on unconscious bias.

A study by Yale University found that even when interviewers received training on objective hiring, both male and female scientists still preferred to hire men when using traditional methods.[16]

Although this is a finding from the male-dominated field of STEM, it stands to reason that similar patterns might be repeated in any environment dominated by one demographic – and that women may well have unconscious bias on their side in pink collar jobs.

Skills testing circumvents this by providing hard data to support recruiters’ hiring decisions and challenge their own biases.

3. Take a structured approach to interviews

If pre-interview testing helps you reduce bias during your screening process, the structured interview approach does this when you meet them face-to-face.

In a traditional unstructured interview, the questions are:

Different for each candidate

Asked in a different order each time

Not necessarily related to the role’s core skills

Lacking clear benchmarks for a “good” response

Naturally, this allows interviewer bias to flourish because you gain uneven data on each candidate. When you’re trying to create equality of opportunity in a role dominated by one gender, this is a big problem.

By contrast, structured interviews dictate questions are:

The same for each candidate

Asked in the same order

Directly related to the core competencies of the role

Judged by pre-agreed criteria

When used in conjunction with prior skills testing, this drastically reduces bias in interviews.[17]

4. Hire for culture add, not culture fit

You may be worried that bringing in a candidate who diverges from the rest of your workforce will throw off your cohesive culture.

This is due to outdated notions of how culture is formed, specifically the idea of “culture fit.”

Traditionally, culture fit in hiring is defined by the “beer test,” an informal test of whether the interviewer would want to go for a beer with the candidate.

This naturally opens the door for bias since the most likable candidate might not be the most skilled one.

It is particularly problematic in roles dominated by one gender. The recruiter may be swayed by confirmation bias, only noticing the ways a candidate conforms to their expectations and not the ways they subvert them.

For instance, when observing a male teacher with a class, a hiring manager might unconsciously look out for moments of impatience or anger and not notice the patience he shows to students.

This notion of culture fit often reproduces the superficial characteristics of existing pink collar workers, which can lead to cliques and dangerous groupthink.

On the other hand, culture add is all about finding a candidate who shares your underlying values but has a different approach than the rest of your team. You can test for culture add during screening and follow up on it during the interview by asking questions like:

You are asked to improve at a task that you thought went well. How would you respond to constructive feedback?

Which company culture suits you best?

How important are empathy and kindness when working in a team?

5. Use skills-based learning to promote internal mobility

Hiring diverse candidates is just the beginning. An essential part of inclusivity in the workplace is ensuring candidates not only have equal opportunities to get into your organization, but to progress through it.

Start by logging new pink collar workers’ performance on skills tests into an internal talent marketplace, software that gives you an overview of the skills resources in your organization.

This helps you identify candidates for promotion or leadership development without bias. You can then provide this training using skills-based learning.

This helps you avoid the phenomenon known as the “pink ghetto”: when pink collar workers become trapped at one level due to limited opportunities for advancement.

It could also help you spot redeployment opportunities for male employees in non-pink collar roles who have the skills to thrive in a HEAL setting.

There are huge benefits to increasing internal mobility this way. Studies show increased internal mobility correlates to higher employee satisfaction; employees who move around internally are three times more likely to be engaged with their work than those who don’t.[18]

6. Promote psychological safety in the workplace

When you’re shaking up the status quo in jobs dominated by one gender, it’s important to create a work environment of psychological safety.

Psychological safety is defined as feeling free to speak one’s mind at work and ask questions and raise concerns without fear of ridicule or retribution.

This is where culture add in hiring becomes especially important. To create a diverse team that nonetheless operates in a psychologically safe way, you need to ensure they share common ground when it comes to the purpose of their work.

Harvard researchers found that when team members had significant personal differences – for instance, in age and gender – without this basis of understanding, they found it less enjoyable to spend time together, had less trust and patience for each other, and experienced more conflict.

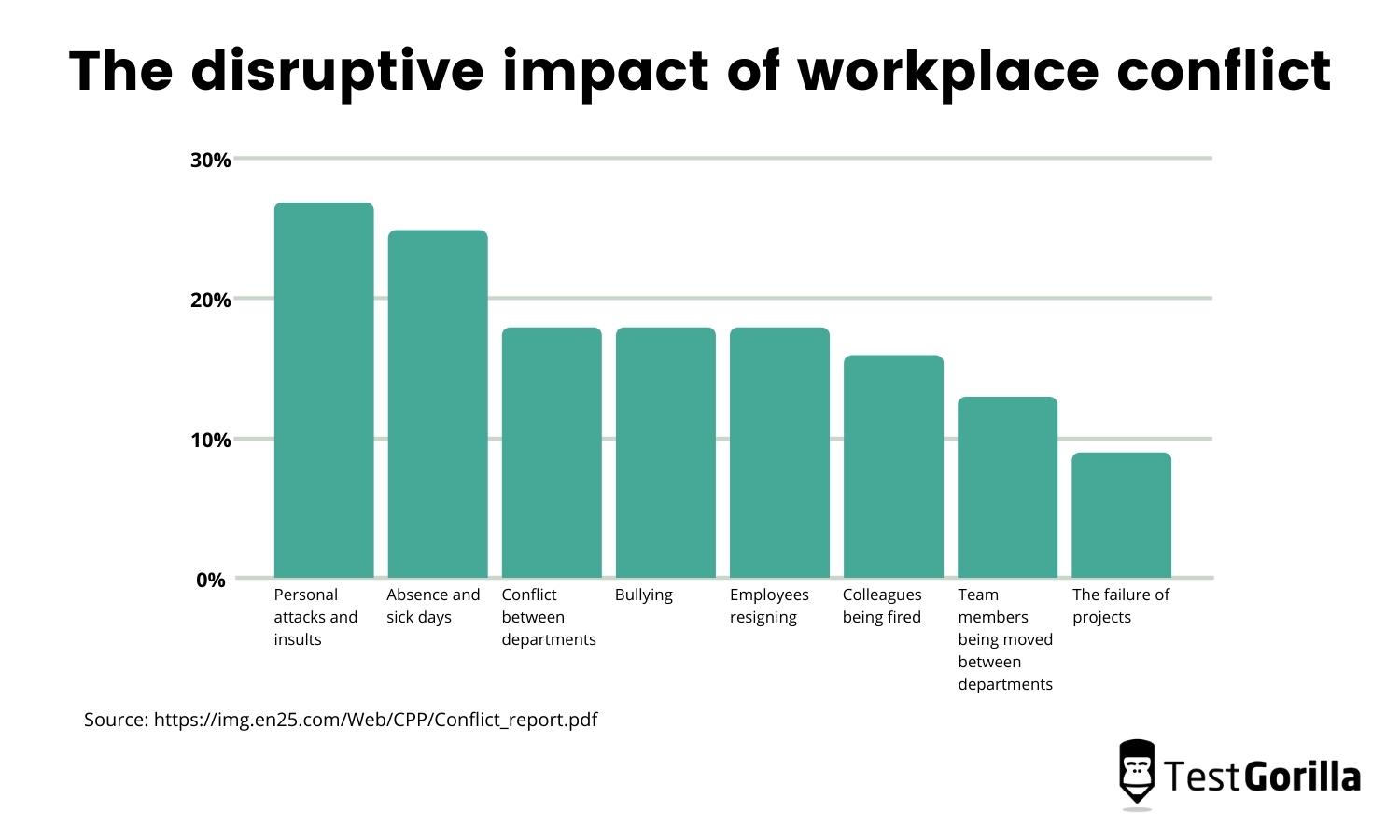

This could severely impact employee wellbeing and could even be expensive for your organization since the common impacts of workplace conflict are wide-ranging:

You can also create a climate of psychological safety by:

Creating multiple avenues for pink collar workers to raise concerns so they can do so without creating conflict

Assembling support groups for employees who are outnumbered in their own professions, such as male nurses or kindergarten teachers

Training your staff in communication skills and active listening, and ensuring managers and senior leaders model these skills

Use skills testing to hire for traditionally pink collar jobs

In this blog, we’ve discussed:

What pink collar jobs are

Where they come from

Why pink collar jobs are so women-dominated

What you can do as an employer to diversify your pink collar workers

In addition to trying out the strategies we’ve outlined above, you should also consider reading more deeply about skills-based hiring and the skills required for jobs in HEAL and other pink collar professions.

To dig deeper into hiring for HEAL, read our blog about how skills-based hiring can reduce male inequality in HEAL roles.

If you’re hiring for a pink collar job that requires empathy, read our guide to hiring for emotional intelligence.

To hire a great fit for the role, regardless of gender, use our Culture Add test to hire the best.

Sources

Fluchtmann, Jonas, et al. (December 2021). “The Gender Application Gap: Do men and women apply for the same jobs?”. IZA Institute of Labor Economics. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339487294_The_Gender_Application_Gap_Do_men_and_women_apply_for_the_same_jobs

“Customer Service Representative Demographics And Statistics In The US”. (2022). Zippia. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.zippia.com/customer-service-representative-jobs/demographics/

Barnartt, Sharon N. (March 1979). “Pink Collar Workers: Inside the World of Women’s Work. Louise Kapp Howe”. American Journal of Sociology. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/226928

“Women in WWI”. The National WWI Museum and Memorial. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.theworldwar.org/learn/women

Waite, Linda J. (February 1976). “Working Wives: 1940-1960”. American Sociological Review. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2094373

Martinez, Anthony; Christnacht, Cheridan. (January 26, 2021). “Women Are Nearly Half of U.S. Workforce but Only 27% of STEM Workers”. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/01/women-making-gains-in-stem-occupations-but-still-underrepresented.html

“Nail Files: A Study of Nail Salon Workers and Industry in the United States”. (November 2018). UCLA Labor Center. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.labor.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/NAILFILES_FINAL.pdf

Ingersoll, Richard; Merrill, Lisa; Stuckey, Daniel. (April 2014). “Seven Trends: The Transformation of the Teaching Force”. Consortium for Policy Research in Education. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1109&context=cpre_researchreports

“Teacher Demographics and Statistics in the US”. (2022). Zippia. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.zippia.com/teacher-jobs/demographics/

Jablonska, Justine. (March 8, 2021). “Seven charts that show COVID-19’s impact on women’s employment”. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/seven-charts-that-show-covid-19s-impact-on-womens-employment

Chaplin, Tara M; Aldao, Amelia. (July 2013). “Gender Differences in Emotion Expression in Children: A Meta-Analytic Review”. Psychol Bull. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3597769/

“Young children may benefit from having more male teachers”. (June 30, 2022). The Economist. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2022/06/30/young-children-may-benefit-from-having-more-male-teachers

“How To Write Gender Neutral Job Descriptions”. (2021). ML6 Search + Talent Advisory. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://ml6.ca/how-to-write-gender-neutral-job-descriptions/

Gaucher, Danielle; Friesen, Justin. (March 7, 2011). “Evidence That Gendered Wording in Job Advertisements Exists and Sustains Gender Inequality”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.sussex.ac.uk/webteam/gateway/file.php?name=gendered-wording-in-job-adverts.pdf&site=7

Bock, Laszlo. (April 7, 2015). “Here’s Google’s Secret to Hiring the Best People”. WIRED. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.wired.com/2015/04/hire-like-google/

Agarwal, Pragya. (December 3, 2018). “Unconscious Bias: How It Affects Us More Than We Know”. Forbes. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/pragyaagarwaleurope/2018/12/03/unconscious-bias-how-it-affects-us-more-than-we-know/?sh=3333fe6e13e7

Bohnet, Iris. (April 18, 2016). “How to Take the Bias Out of Interviews”. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://hbr.org/2016/04/how-to-take-the-bias-out-of-interviews

“Skill Building in the New World of Work”. (2021). LinkedIn Learning. Retrieved May 3, 2023. https://learning.linkedin.com/content/dam/me/business/en-us/amp/learning-solutions/images/wlr21/pdf/LinkedIn-Learning_Workplace-Learning-Report-2021-EN-1.pdf

Related posts

Hire the best candidates with TestGorilla

Create pre-employment assessments in minutes to screen candidates, save time, and hire the best talent.

Latest posts

The best advice in pre-employment testing, in your inbox.

No spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

Hire the best. No bias. No stress.

Our screening tests identify the best candidates and make your hiring decisions faster, easier, and bias-free.

Free resources

This checklist covers key features you should look for when choosing a skills testing platform

This resource will help you develop an onboarding checklist for new hires.

How to assess your candidates' attention to detail.

Learn how to get human resources certified through HRCI or SHRM.

Learn how you can improve the level of talent at your company.

Learn how CapitalT reduced hiring bias with online skills assessments.

Learn how to make the resume process more efficient and more effective.

Improve your hiring strategy with these 7 critical recruitment metrics.

Learn how Sukhi decreased time spent reviewing resumes by 83%!

Hire more efficiently with these hacks that 99% of recruiters aren't using.

Make a business case for diversity and inclusion initiatives with this data.