Most hiring managers today know that whether or not a candidate is skilled and motivated has nothing to do with their gender.

And yet, as you probably guessed if you’re reading this blog, having this belief doesn’t automatically translate to gender equity in hiring.

Maybe you’re not seeing many applications from women and want to understand why, or perhaps you’ve noticed that women don’t often make it through your recruiting process to become new hires.

You might have heard that skills-based hiring increases diversity (in 91.1% of organizations that adopt it, to be exact), and you want to know if it can help you level the playing field for women candidates.

In this blog, we explore the gender application gap – what it is and what could be causing it – and discuss what skills-based hiring can do to minimize its impact on your recruitment.

Table of contents

- What is the gender application gap?

- What’s driving the gender application gap?

- Switch to a skills-based approach to help close the gender application gap

- Adopting skills-based hiring isn’t a silver bullet: We need widespread change

- Lead the charge for equality of opportunity in recruiting by switching to skills-based hiring

- Sources

What is the gender application gap?

The “gender application gap” refers to the differences between how men and women apply for roles. It’s observable in many different areas, including:

Which jobs they apply to

How often they apply

When they apply and when they hold back

A large 2021 study found that men and women show significant differences in the types of roles that they apply for, even when the groups in question have very similar attributes.

For instance, the average woman sends almost 12% more applications to service occupations than the average man; she also sends 4.7% fewer applications to machine occupations and 6.1% fewer to craft occupations. In addition, women are less likely to apply for jobs in construction, sending 5.6% fewer applications.

The study notes that because the groups are compared based on similarities including past education and occupation, these differences can’t solely be explained by men or women being more likely to have education or experience in a particular occupation or industry.

These differences contribute to the gender employment gap and, consequently, the gender pay gap, which in 2022 stood at women earning $0.82 for every $1 made by a man.

They could even help explain why the gender pay gap persists despite laws against wage discrimination in the workplace.

This is because, as the study pointed out, women frequently target jobs with lower wages. In fact, the authors attributed more than 70% of the gender pay gap and potentially many other gender-related gaps in the labor market to this difference.

As well as often applying for different roles to men, women also apply to jobs less frequently across the board compared to their male counterparts.

According to a LinkedIn study, women apply to 20% fewer jobs than men, though they are 16% more likely than men to get hired after applying for a job, and this rises to 18% for senior roles. They were also 26% less likely to ask for a referral from a contact at their target company.[1]

Blind spots in gender application gap reporting

As is probably clear from the way we’ve talked about it so far, the “gender application gap” is almost exclusively used in a binary way: To refer to the differences between men’s and women’s application behaviors. There’s still very little reporting or data on application trends among other gender identities, such as non-binary people.

This makes it harder to unpack the broader implications of gender on application trends in a more inclusive way and may indeed mask an application gap between cisgender and transgender candidates. This echoes difficulties around ascertaining the impact of gender inequality on trans employees in other areas, such as with pay.[2]

As a result, we’ll mainly focus on the gender application gap as it affects the self-identifying men and women that have participated in the relevant studies.

Let’s start by discussing the factors that are driving these differences in the ways women apply for jobs.

What’s driving the gender application gap?

The most common reason given for gender differences in job applications is that women are not as confident in their skills as men.

You know the stat: An internal report at Hewlett-Packard in the 2010s famously said that men apply for a role when they meet 60% of the qualifications, but women apply only if they meet 100% of them. However, you might not know that this figure was disputed by Harvard Business Review in 2014.

Contrary to Hewlett-Packard’s findings, Harvard’s study found that only 10% of women and 12% of men held back from applying to jobs because they didn’t think they could do them well.[3]

They found that the top reason for women holding back in job applications was much more practical: They believed that the qualifications listed in the job ad were non-negotiable, and they would simply not be considered without them – regardless of whether they believed they could do the role at hand.

The author posited that women were therefore held back more by mistaken perceptions about the hiring process than by their own “lack of confidence.” She declared that, by and large, women see themselves as being realistic when holding back from applying, not unconfident.

But do we have to see this as an either/or situation? Either women suffer from the impostor syndrome and men suffer from the Dunning-Kruger effect (and are rewarded for it), or these differences are down to mistaken beliefs about what “qualifications” mean.

You can probably tell from our tone, but we don’t think it needs to be one or the other. We think it’s much more nuanced than that.

Here are some of the factors we think are at play in causing the gender application gap.

Negative self-perception

While we don’t necessarily believe that it’s the driving factor behind the gender application gap, there is evidence that negative self-perception plays a role – at least in some cases.

For instance, a recent UK study found that men were more willing to apply for roles than similarly qualified women. The men believed that they met the overall requirements whereas the women didn’t. Significantly, however, this belief only persisted among less-qualified groups of applicants: The gender difference disappeared among more qualified participants.

So, lower-qualified women might actually rate their own skills lower than similarly qualified men rate their own, but as we’ve seen, this trend doesn’t extend to other groups.

A more significant factor may be that women are anticipating discrimination from hiring managers.

Anticipating discrimination from recruiters and workplaces

It’s no secret that women experience discrimination in the workplace. Randstad’s Gender Equality in the Workplace 2022 report found that 72% of women had either encountered or witnessed inappropriate behavior from male colleagues, and 67% had experienced gender discrimination in some form.

These negative experiences may justifiably cause women to expect discrimination from hiring managers, and they’re not wrong. The LinkedIn study cited above found that recruiters were 13% less likely to click on a woman’s profile when it showed up in a LinkedIn search.

Clearly, women have reason to believe they have to be 100% qualified to stand out.

The anticipation of discrimination may also cause them to steer clear of male-dominated organizations or industries. Remember earlier when we said that women were less likely to apply for construction roles? The Randstad report found that almost half (45%) of women in construction said sexual harassment had either a small or large impact on their careers.

Another related reason why women might hold back from applying to some roles is the fear of failure – or, to be more specific, the fear that their failures will be held against them.

Fear of failures being held against you

The Harvard study indicated that 22% of women cite the fear of failure as the biggest reason that held them back from applying for a role, while only 13% of men said the same.

The fear of failure leaving a mark on your record as a woman isn’t unrealistic, particularly if you are additionally marginalized, for instance, by race. Research has shown that Black women are evaluated more harshly in situations of organizational failure than Black men, White men, and White women.

The researchers suggested that while White women and Black men benefited from at least one predominant identity that was associated with leadership (i.e. being White or male), Black women’s dual marginalization meant that they experienced especially negative consequences from failure.

While we have plenty of data on how the anticipation of discrimination affects women’s behavior, this may also affect people of diverse genders, such as non-binary or trans people.

Indeed, 37% of transgender people said that they have experienced discrimination when looking for work, and similarly to cis women, this persists despite laws enacted against it.[4] A study in Sweden found that despite legal protections against transphobia, trans people still experienced discrimination in the labor market.[5]

While there is not yet fully-inclusive data on gender application gaps, these findings suggest that application gaps exist far beyond the normative gender binary.

Disproportionate caring responsibilities

The final factor we discuss here (though we don’t think this is by any means an exhaustive list) is caring responsibilities.

Historically, long-term absences from the workforce have been seen as a red flag by recruiters, and these are often caused by caring responsibilities. Women are disproportionately affected by this negative bias due to the widespread societal expectation that care work is a woman’s role, one that was put into particular focus during the pandemic.

A shocking McKinsey study found that during the Covid-19 pandemic, one in four women were considering leaving the workforce or downshifting their careers compared to one in five men, with this disparity being particularly pronounced among the parents of children under ten.

There are many potential explanations for this.

One of them is the gender pay gap. As mentioned above, women earn less on average than men and therefore may feel pressure to prioritize their husbands’ careers for more stability in times of economic crisis since they’re the higher earners.

Another factor is that lockdown measures removed most childcare options for working parents.

With children taking remote classes rather than going out to school or preschool, parents had to pick up the slack, and this disproportionately fell on mothers. The first weeks of lockdown in the UK saw women take on two-thirds more childcare duties per day than men.

Finally, the experience of being at home during lockdown may simply have altered women’s perspectives on their priorities.

Many women may have decided after the lockdown that they want to spend more time with their children on a permanent basis. This may be particularly true in cases where part-time and remote work is available as a long-term option or where money isn’t a pressing concern, so the pressure to work isn’t as immediate.

In summary, there is no single cause for the gender application gap, but it is a combined result of factors such as:

Negative self-assessment of women’s skills and qualifications

Anticipation of failure partly due to bias during the hiring process

Fear of their failures being remembered longer than their male counterparts

The disproportionate effects of caring responsibilities on women’s careers

The question now is: What can you do to help alleviate this gap?

Switch to a skills-based approach to help close the gender application gap

There is evidence that skills-based hiring reduces bias during the hiring process. A study of more than 2,000 successful job applicants showed that the number of women hired into senior roles increased by almost 70% when skills-based methods were used.

But which aspects of the skills-based hiring approach make it so effective in narrowing the gender application gap?

Moving away from resumes

Historically, the resume has been front and center of traditional hiring methods.

Employers use it to ascertain what responsibilities a candidate has held, spot any gaps in employment, and screen out candidates based on a lack of qualifications, like a four-year degree. They also use resumes to screen in candidates using specifically worded “key skills.”

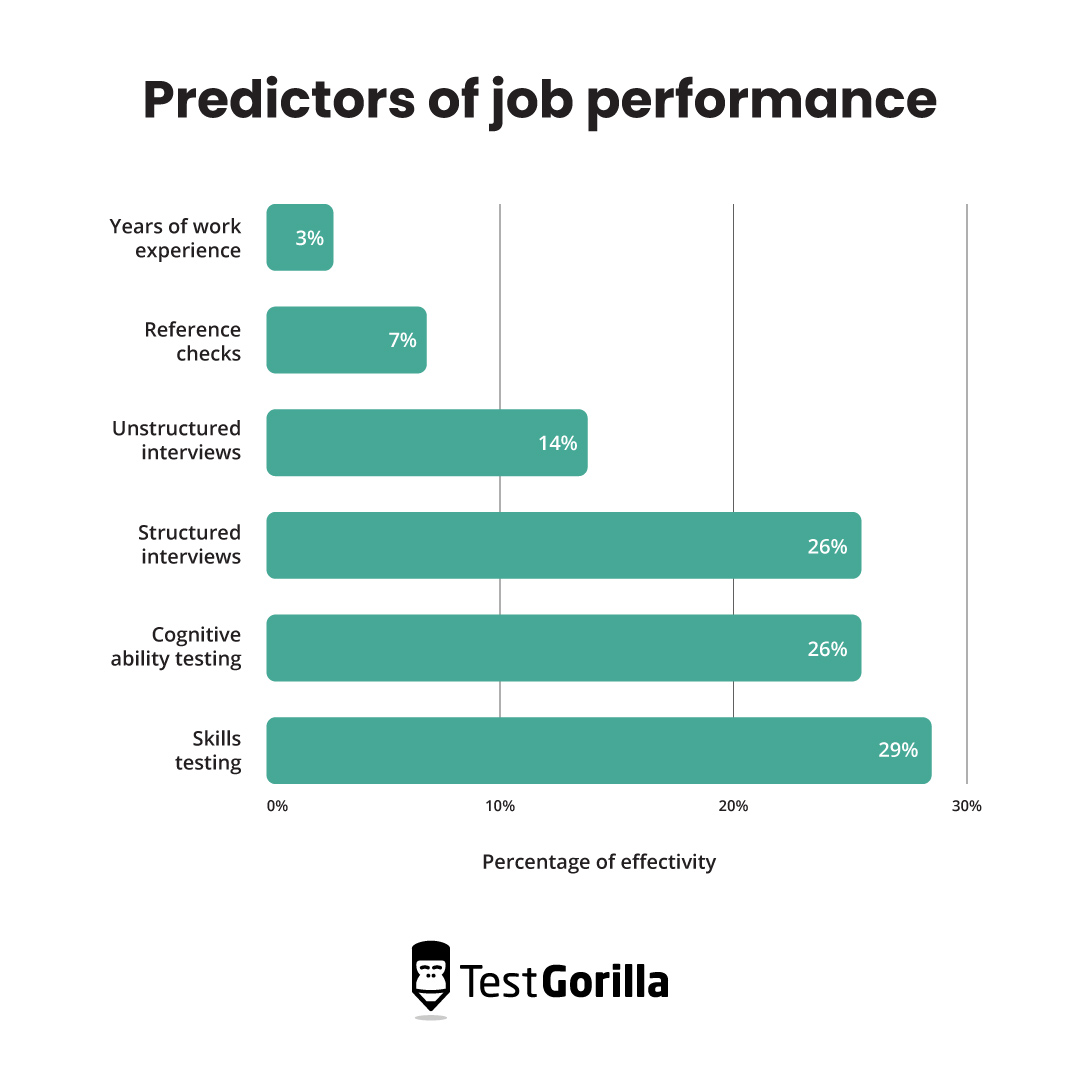

However, many of these metrics are actually highly unhelpful when it comes to making a great hire. Years of work experience, for example, only predict job performance with 3% accuracy according to a study at Google. Meanwhile, skills testing was almost ten times as effective.[6]

Not only do resumes not provide useful information, but they also create ample opportunity for negative self-perception to inhibit a candidate’s progress.

As we’ve noted, while it may not be the driving factor in the gender application gap, women do sometimes display less confidence in their own abilities than similarly qualified men, especially among less qualified candidates. The requirement to boast on a cover letter or list the skills that they are proficient in on a resume puts these candidates at a disadvantage.

Resumes also throw the door wide open for bias right at the start of your hiring process.

Companies hiring for STEM roles rated candidates with female and minority sounding names lower than candidates with White male-sounding names even when they had the same or higher GPA, and female and minority candidates also received less credit for prestigious internships in all fields.

When women anticipate discrimination from hiring managers, they know that the resume is a key source for it. We, therefore, advocate replacing resume screening with pre-interview skills assessments to directly test candidates on the core competencies of the role.

This enables you to set the parameters for how good a skill needs to be to get noticed, which may encourage candidates, who would usually hold back, to throw their hats into the ring.

It also reassures candidates who are nervous about being discriminated against that there is less opportunity for bias in your hiring process.

Plus, as the Google study shows, skills tests are almost ten times more effective at predicting job performance than looking at years of experience on a resume. As well as pulling in a more diverse pool of applicants, skills tests are also likely to help you make better hiring decisions.

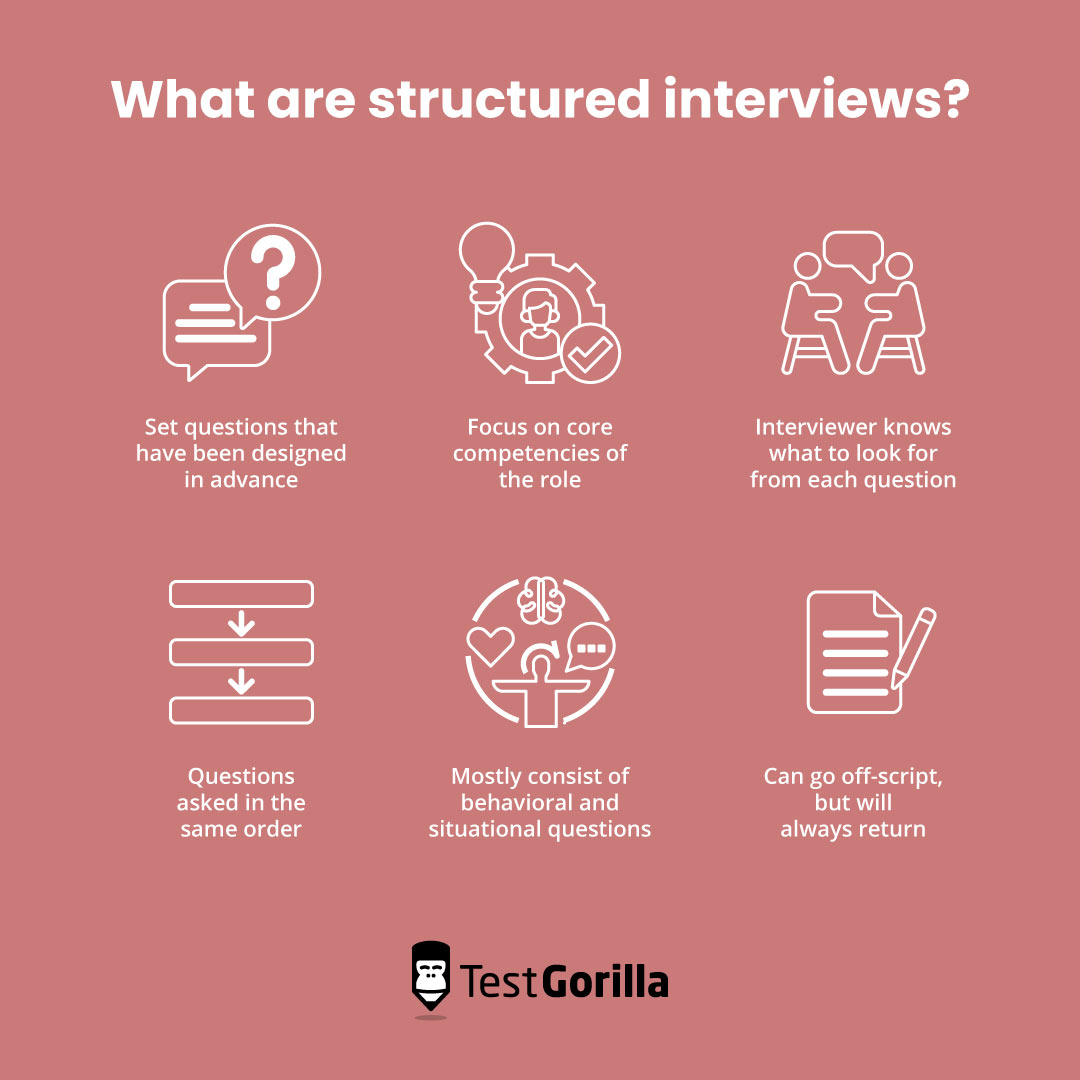

Switching to structured interviews

Another place that you can alleviate candidates’ anxieties about bias in hiring is with your interview process.

Traditional hiring uses unstructured interviews in which hiring managers improvise the questions they ask candidates and don’t agree on the criteria for a “good” answer beforehand.

This opens the door for interviewer bias since the interviewer may not even realize that their unconscious beliefs about women cause them to ask different questions toward male and female candidates or evaluate them differently.

Take the issue of confidence. It’s a trait that’s talked about repeatedly in hiring, but it’s interpreted very differently in men versus women.

Researchers have found that even among similarly high-performing workers, women’s self-confidence does not easily influence others’ perception of them as it does for men. Instead, women also have to appear caring and prosocial for their confidence to make others trust them, and their self-reported confidence doesn’t correlate with how confident they appear to others.[7]

These kinds of biases around women’s confidence could easily impact an unstructured interview.

For example, the interviewer might unconsciously assume that a woman candidate is less adept than the man they previously interviewed. This might cause them to ask more difficult, harder-hitting questions and to be skeptical of the woman candidate’s self-confidence in her answers, leading them to judge her overall performance more harshly.

Structured interviews, on the other hand, require that interviewers ask the same questions in the same order and use the same pre-agreed criteria for acceptable answers.

This reduces the opportunity for bias to affect women candidates’ outcomes, particularly when supported by hard data from pre-interview skills testing.

Even if you do all of this perfectly, there is only so much that one organization can do to alleviate the gender application gap. After all, skills-based hiring cannot address the inequalities in caring responsibilities that keep women from returning to work, nor can it eradicate the fear of discrimination in male-dominated industries.

To see the gender application gap close entirely, we need more than organizational change: We need widespread change across industries.

Adopting skills-based hiring isn’t a silver bullet: We need widespread change

Changing how women are hired does not intrinsically change which roles they’re applying to, since the different ways in which men and women are socialized growing up may contribute to the interests and skills they develop and nurture as they get older.

This is shown in the data: The study of 2,000 job applicants cited above found that even with a skills-based hiring approach, women succeeded at higher rates in some industries than others, evidently due to women being more likely to have skills or interests in certain areas due to social conditioning.

For example, women were particularly likely to succeed in publishing, where they accounted for 81% of senior hires. They also gained 67% of top roles in education, 65% in health, and 61% in the charity sector.

This may partially be accounted for by the fact that, as mentioned above, women are expected to take on more nurturing roles in their personal lives. This would certainly help to give them the skills to succeed in health and education.

In regard to publishing, women are encouraged to engage with literature from a young age in a way that most men are not. Deloitte found that fathers are less likely to read themselves, so children are less exposed to male reading models, and fathers are less likely to read to their sons than they are to daughters.

This produces a snowball effect. Not seeing themselves represented in the current generation of workers in a given industry, both women and men are unlikely to seek opportunities in it. This leads to similar mindsets in future generations.

As we’ve seen above, people may also expect harassment in an industry dominated by the opposite gender. This then entrenches the problem as time goes on.

Change needs to happen on the societal level, then, to stop conditioning people to see any role as a “man’s job” or a “woman’s job,” and eliminate the dominance of a single gender in any one industry. Part of this comes from industries pushing the envelope, with recruiters unlearning old habits.

So, in addition to the widespread adoption of skills-based hiring processes, what changes do we need to see across industries to alleviate the gender application gap?

Here are four ideas.

1. Actively address sexism and unconscious bias

As we’ve discussed, many women hold themselves back from applying for a role because they anticipate that discrimination from hiring managers might take them out of the running, and they’re not always wrong.

Yale researchers found that even in cases where interviewers received training on objective hiring, both male and female scientists still preferred to hire men.[8]

Tackling sexism and unconscious bias in hiring, therefore, needs to be a more prominent and widespread part of the hiring process.

That means more organizations supporting recruiters to make unbiased decisions – and not just through individual bias training, which puts the burden for tackling bias on individual recruiters.

Instead, organizational change in this area might look like:

Widespread adoption of skills testing to support hiring managers’ decision-making process with hard data

Industry-wide rejection of resumes as a screening tool

Making it the norm to provide internal diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives to ensure that women thrive long-term as well as during the hiring process

2. Create transparency about the hiring process

As organizations adopt bias-reducing processes in their hiring, they also need to be more transparent about their processes. As we’ve seen above, misunderstandings about “required” qualifications contribute significantly to the gender application gap.

An important aspect of this transparency is including the salary range for each role in your job ads.

Many employers still neglect to do this, which disadvantages women during the negotiation process. One UK study found that men were 20% more likely to negotiate their salary during an interview, while one-fifth of women had never negotiated their salary at all.

It should also become the norm for organizations to publicize how their hiring processes work. You might do this at the bottom of your job ads, on a dedicated page on your website or careers portal, or both. Answer key questions like:

What is the recruitment timeline usually like?

How is each stage assessed?

What anti-bias protocols are you using?

When can candidates expect to hear back from you?

By doing this, organizations can eliminate many of the obstacles we’ve discussed above while also actively encouraging marginalized candidates to apply by reassuring them that they are working to eliminate bias.

It really works: A study of more than 48,000 applications to UK graduate schemes showed that a skills-based hiring approach increased the number of female applicants by 17%.[9]

This can even carry through to the interview stage. If you publicize that you use structured interview techniques, women can be more confident that bias will be eliminated.

It may work particularly well if you emphasize that you are hiring for culture add over culture fit. Instead of worrying about having to “fit” into a culture dominated by another gender, candidates of all identities will feel emboldened by the invitation to add something new to it.

These tactics to promote transparency don’t only help level the playing field for women. They create a better candidate experience for all candidates, which has positive effects on both hiring and retention.

3. Use skills-based methods to develop employees, not just hire them

The third shift that we believe would benefit gender equity in the recruitment process is a more widespread understanding that skillsets are not fixed at the moment of recruitment, but are constantly developing with employers having a hand in that development.

Investing in your employees through upskilling and reskilling initiatives provides a significant incentive for top candidates to leave their current jobs and work for you. Studies show that the number one reason people leave their jobs is a lack of learning and development opportunities in their current roles.

Not only that, it shows hesitant candidates who don’t meet all the qualifications (or don’t think they do) that there are mechanisms in place for them to learn the skills that they might be lacking upon entering the workforce.

Skills-based methods can help you here – they go hand in hand with employee development by providing the tools to:

Identify what skills employees have when they are hired

Identify what skills are required by their teams and departments

Track employees’ progress as they embark on developing their skills

The effect of skills-based upskilling initiatives is to create pathways for progression for women because it prepares them to take on extra responsibilities and move up in the workforce.

This ultimately helps employers carry the commitment to diversity from hiring through to retention. You’ll not only hire more women, but see them represented throughout your workforce as skills training encourages them to stay for longer and move up the ranks.

The data supports this view: 70% of employees who receive a promotion within three years of being hired plan to stay with their employers long-term, compared to just 45% of those who don’t.

4. Support all working parents, not just working mothers

Finally, organizations should support all working parents equally and remove or alter policies that allow for caring responsibilities to disproportionately impact women’s careers, a phenomenon known as “the motherhood penalty.”

There are many strategies available for you to support parents in the workplace, one of the most significant of which is extending your parental leave policy.

The United States is one of the least generous of the world’s richest countries when it comes to paid parental leave. Neither mothers nor fathers in America are covered by any national paid leave policy; the only available leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act is unpaid – and that only covers around 60% of Americans.

Some states do have their own paid family leave policies, but by and large, parents in the US experience unacceptable pressure to return to work after having a child. Many parents feel forced to quit their current roles instead of simply returning at their own pace.

This means that not only can fairer parental support policies differentiate you from other employers, but they can also boost your productivity over the competition.

Our suggested best practices for implementing better parental leave policies include:

An organized departure process

A clear communication plan

A robust and meaningful re-onboarding process

One way you can carry parental support policies through after the birth of employees’ children is by offering free or subsidized childcare facilities at your office.

This would not only help boost the number of parents returning to work after family leave, but it can also aid diversity as the cost of childcare is prohibitive for most families at more than $1,300 per month in the US.

Many successful companies have adopted this policy, including clothing giant Patagonia, whose chief human resources officer said he now considers childcare a “bedrock employee benefit.”[10]

You won’t regret prioritizing parents’ needs in this way. A 2020 study found that organizations that make significant investments in their employees and their families experience 5.5 times more revenue growth thanks to effects like greater innovation, better retention, and increased productivity.

Lead the charge for equality of opportunity in recruiting by switching to skills-based hiring

In this blog, we’ve covered:

What the Gender Application Gap is

The different factors that could be causing it – and the debates about each of them

How skills-based hiring can (and can’t) fix the problem

While skills-based hiring might not entirely eliminate the gender application gap, it’s a very important start, and the more that skills-based hiring practices become the norm in the recruitment industry, the closer we are to achieving equality of opportunity for all.

To get started, read our blog about overcoming unconscious bias in your hiring practices, or perhaps use our Culture Add test in your next round of hiring.

If you want to dive into diversity, equity, and inclusion strategy, read our guide to best practices to make your company more diverse and inclusive.

Sources

Ignatova, Maria. “New Report: Women Apply to Fewer Jobs Than Men, But Are More Likely to Get Hired”. (March 5, 2019). LinkedIn Talent Blog. Retrieved March 03, 2023. https://www.linkedin.com/business/talent/blog/talent-acquisition/how-women-find-jobs-gender-report

Christen, Alex. “How does gender pay gap reporting affect transgender employees?”. (July 13, 2018). Personnel Today. Retrieved March 03, 2023. https://www.personneltoday.com/hr/how-does-gender-pay-gap-reporting-affect-transgender-or-non-binary-employees/

Mohr, Tara Sophia. “Why Women Don’t Apply for Jobs Unless They’re 100% Qualified”. (August 25, 2014). Harvard Business Review. Retrieved March 03, 2023. https://hbr.org/2014/08/why-women-dont-apply-for-jobs-unless-theyre-100-qualified

Granberg, Mark. “Transgender people suffer discrimination in the job market”. (October 8th, 2020). London School of Economics Blog. Retrieved March 03, 2023. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2020/10/08/transgender-people-suffer-discrimination-in-the-job-market/

Granberg, Mark; Anderson, Per A; Ahmed, Ali. “Hiring Discrimination Against Transgender People: Evidence from a Field Experiment”. (August 2020). Labour Economics. Retrieved March 03, 2023. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0927537120300646

Bock, Laszlo. “Here’s Google’s Secret to Hiring the Best People”. (April 7, 2015). WIRED. Retrieved March 03, 2023. https://www.wired.com/2015/04/hire-like-google/

Guillen, Laura. “Is the Confidence Gap Between Men and Women a Myth?”. (March 26, 2018). Harvard Business Review. Retrieved March 03, 2023. https://hbr.org/2018/03/is-the-confidence-gap-between-men-and-women-a-myth

Agarwal, Pragya. (December 3, 2018). “Unconscious Bias: How It Affects Us More Than We Know”. Forbes. Retrieved March 03, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/pragyaagarwaleurope/2018/12/03/unconscious-bias-how-it-affects-us-more-than-we-know/?sh=3333fe6e13e7

“Skills-based’ hiring drives 65% uplift in number of women hired onto graduate schemes”. (October 26, 2022). FE News. Retrieved March 03, 2023. https://www.fenews.co.uk/employability/study-replacing-cvs-with-skills-tests-sees-more-women-land-graduate-jobs/

Anderson, Bruce. (September 10, 2019). “Why Patagonia CHRO Dean Carter Sees Onsite Child Care as a Bedrock Benefit”. LinkedIn Talent Blog. Retrieved March 03, 2023. https://www.linkedin.com/business/talent/blog/talent-engagement/why-patagonia-offers-onsite-child-care

Related posts

Hire the best candidates with TestGorilla

Create pre-employment assessments in minutes to screen candidates, save time, and hire the best talent.

Latest posts

The best advice in pre-employment testing, in your inbox.

No spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

Hire the best. No bias. No stress.

Our screening tests identify the best candidates and make your hiring decisions faster, easier, and bias-free.

Free resources

This checklist covers key features you should look for when choosing a skills testing platform

This resource will help you develop an onboarding checklist for new hires.

How to assess your candidates' attention to detail.

Learn how to get human resources certified through HRCI or SHRM.

Learn how you can improve the level of talent at your company.

Learn how CapitalT reduced hiring bias with online skills assessments.

Learn how to make the resume process more efficient and more effective.

Improve your hiring strategy with these 7 critical recruitment metrics.

Learn how Sukhi decreased time spent reviewing resumes by 83%!

Hire more efficiently with these hacks that 99% of recruiters aren't using.

Make a business case for diversity and inclusion initiatives with this data.